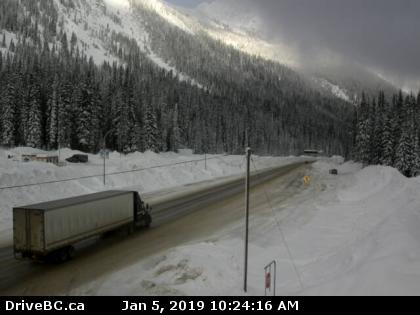

This one captures, to me, captures both the wonder and danger of winter travel in the mountains of British Columbia – the magnificence of the setting sun around the corner and the first hints of the storm that’s about to hit.

I hear those two words together – Rogers Pass – and I automatically think of the lyrics to a Tom Cochrane song, the history and the tragedy of this historic point in Canada.

Can you remember the trip we took

Tom Cochrane – The Secret is to Know When to Stop

In the Malibu to the west coast

We drove through a rainbow up on Roger’s Pass

They never thought you’d get that close

I always have, and still, do hear that line in this song as “They never thought he’d get that close.” Always thought Tom mas making a historical reference to the fact that the power brokers at the Canadian Pacific Railway really did not think Major A.B. Rogers would find a pass when they offered up $5,000 (about $120,000 equivalent today) and the right to name the pass to him.

He almost didn’t.

Hired in April 1881 Rogers started out from what is now Revelstoke, up the Illecillewaet River. Running out of food, Rogers and his party almost reached the summit but turned back feeling reasonably confident that a pass existed. Rogers returned the following year, 1882, from the east and reached a point where he could see where he had stopped the previous season, confirming that the pass existed and was good enough for the railway rapidly approaching across the prairies. Rogers was reluctant to cash the $5000 cheque, and instead framed it for his wall until CPR General Manager William Cornelius Van Horne offered him a gold watch as an incentive to cash it.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The pass receives some of the heaviest snowfall amounts in the country and was the site of Canada’s worst avalanche disaster, on March 10th, 1910, when 62 men were killed clearing the snow from the rail line.

The CPR eventually abandoned the pass in 1916 after boring the five-mile-long Connaught Tunnel through Mount Macdonald.

The winter of 1909–1910 provided conditions particularly conducive to avalanches… Three days later on the evening of

March 4 work crews were dispatched to clear a big slide which had fallen from CheopsMountain, and buried the tracks just south of Shed 17. The crew consisted of a locomotive-driven rotary snowplow and 63 men. Half an hour before midnight as the track was nearly clear, an unexpected avalanche swept down the opposite side of the track to the first fall. Around 400metres of trackwere buried. The 91-ton locomotive and plow were hurled 15metres to land upside-down. The wooden cars behind the locomotive were crushed and all but one of the workmen were instantly buried in the deep snow. The only survivor was Billy Lachance the locomotive fireman who had been knocked over by the wind accompanying the fall but otherwise remained unscathed.Many of the dead were found standing upright, frozen in position, reminiscent of Pompeii.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia